12 months on—and one questionable set of tweets aside—the AMD of today is almost unrecognisable.

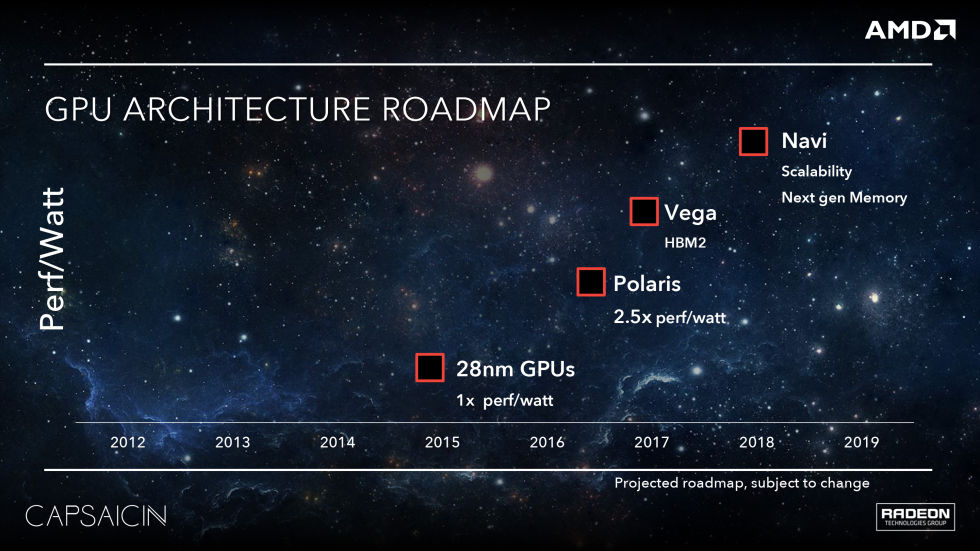

Its range of Fury graphics cards, released at the tail end of 2015, have proven to be potent performers, even if they come up just shy of total graphics card dominance. Under DirectX 12, AMD sometimes even comes out on top. There's talk of £1 billion in future revenue coming in for three new gaming processors (hello, PlayStation 4K and Nintendo NX), while hopes are high for Zen, the firm's upcoming CPU architecture that promises to undo the damage done by the lacklustre Bulldozer architecture released in 2011. Most importantly of all, AMD has Polaris, a new graphics architecture and manufacturing process that puts an end to five long years of 28nm graphics cards. Hell, even AMD's graphics drivers are good now.

Notably absent from that string of accomplishments is any comment, or criticism of, its chief competitor Nvidia. For the first time in a long time, AMD has a range of products that it can be proud of, and a GPU roadmap it can count on—no Nvidia-bashing required. And for Roy Taylor, AMD's long-standing corporate mouthpiece who has been famously and publicly critical of Nvidia (where he worked for over a decade), it's a much-needed change in tack.

"If you're gonna have a competitor, make it a good one," said Taylor in an interview with Ars at the VR World Congress expo in Bristol. "In the past we used to reference our competition, but now it's just about us. I was so pleased at the positive approach [Nvidia] took when we suggested the VR Council. We also work with them in Khronos and on Vulkan. There's no need for us to be antagonistic. They're a worthy competitor, we're doing some things we're proud of that put us in a leadership position, and we'll continue to compete with them to the benefit of everybody."

That competition will come to a head later later this year when AMD's Polaris graphics architecture will compete with Nvidia's Pascal architecture. Both are based on a 14nm manufacturing process, and both promise to dramatically increase the performance per watt of their graphics cards. The key differentiator is market positioning: Pascal is likely to be a high-end part with fast GDDR5X memory, while AMD has confirmed—despite earlier comments to the contrary—that Polaris will be aimed at "the mainstream desktop and high-end gaming notebook segment."

That's not to say Polaris will be slow. Early rumours point to Polaris 10, the more powerful version of the chip, comparing favourably with Nvidia's GTX 980 Ti, which would mark a huge shift in the price-to-performance ratio. Even if that's true, and if Polaris really does come in at a £200/$300 price point, the question is: why offer such power in a mainstream part?

"If you look at the total install base of a Radeon 290, or a GTX 970 or above [the minimum specs required for VR], it's around 7.5 million units," explained Taylor. "But the issue is that if a publisher wants to sell a £40/$50 VR game, there's not a big enough market to justify that yet. We've got to prime the pumps, which means somebody has got to start writing cheques to big games publishers. Or we've got to increase the install TAM [total addressable market].

"The reason Polaris is a big deal," continued Taylor, "is because I believe we will be able to grow that TAM significantly. I don't think Nvidia is going to do anything to increase the TAM, because according to everything we've seen around Pascal, it's a high-end part. I don't know what the price is gonna be, but let's say it's as low as £500/$600 and as high as £800/$1000. That price range is not going to expand the TAM for VR. We're going on the record right now to say Polaris will expand the TAM. Full stop."

AMD is betting on VR, and it's betting hard. Compelling content for VR isn't quite here yet—"we don't have something that's so compelling that you just can't wait to get home, or take days off sick, to play," says Taylor—but when it does, and when a regular, mainstream consumer goes to an electronics store buy a PC to get that VR experience, AMD wants it to be powered by its GPU at an accessible price. It's a big gamble, one that depends on numerous stakeholders each playing their part. That's not to mention that just because Nvidia is rumoured to be launching a high-end part now, it can't release a high-powered mainstream part in the future—or simply just drop the price of its high-end cards.

"Are we afraid of our competitors? No, we're completely unafraid of our competitors," said Taylor. "For the most part, because—in the case of Nvidia—they don't appear to care that much about VR. And in the case of the dollars spent on R&D, they seem to be very happy doing stuff in the car industry, and long may that continue—good luck to them. We're spending our dollars in the areas we're focused on."

reader comments

34