If our early primate ancestors first became human when they learned to cook, then mankind advanced yet again once we evolved beyond the push-button cell phone. The T9 interface by which those twelve keys were used to peck out the alphabet was rendered obsolete by Apple’s smooth glass screen. Texts, once reserved for essential information only, can today be used to end relationships.

Apple’s predictive text algorithms for iPhone were capable of displaying options for words even the most die-hard T9’er wouldn’t have hazarded to type. Now, even that early Apple technology is quickly overshadowed by the predictive text banner that displays multiple, changing options for words–anticipating our very thoughts. That is, of course, unless you have a dirty mouth.

Apple’s predictions are, for the most part, incredibly accurate–except in the case of profanity. And that is by design. If its phone’s computer is so undeniably more sophisticated than those powering the Apollo-era space shuttles that took men to the moon, why is its sensibility still half a century behind?

Go ahead, try typing out a word of profanity. We’ll pretend you haven’t done it before. You’ll have to manually input the entire ducking word (unless you are OK with exactly that kind of autocorrect). But the exclusions from Apple’s predictive text algorithm do not end there. In 2013, The Daily Beast found 14,000 words that weren’t recognized by Apple’s algorithm, spanning from profanity to everyday words encumbered by outmoded social taboos, like tampon.

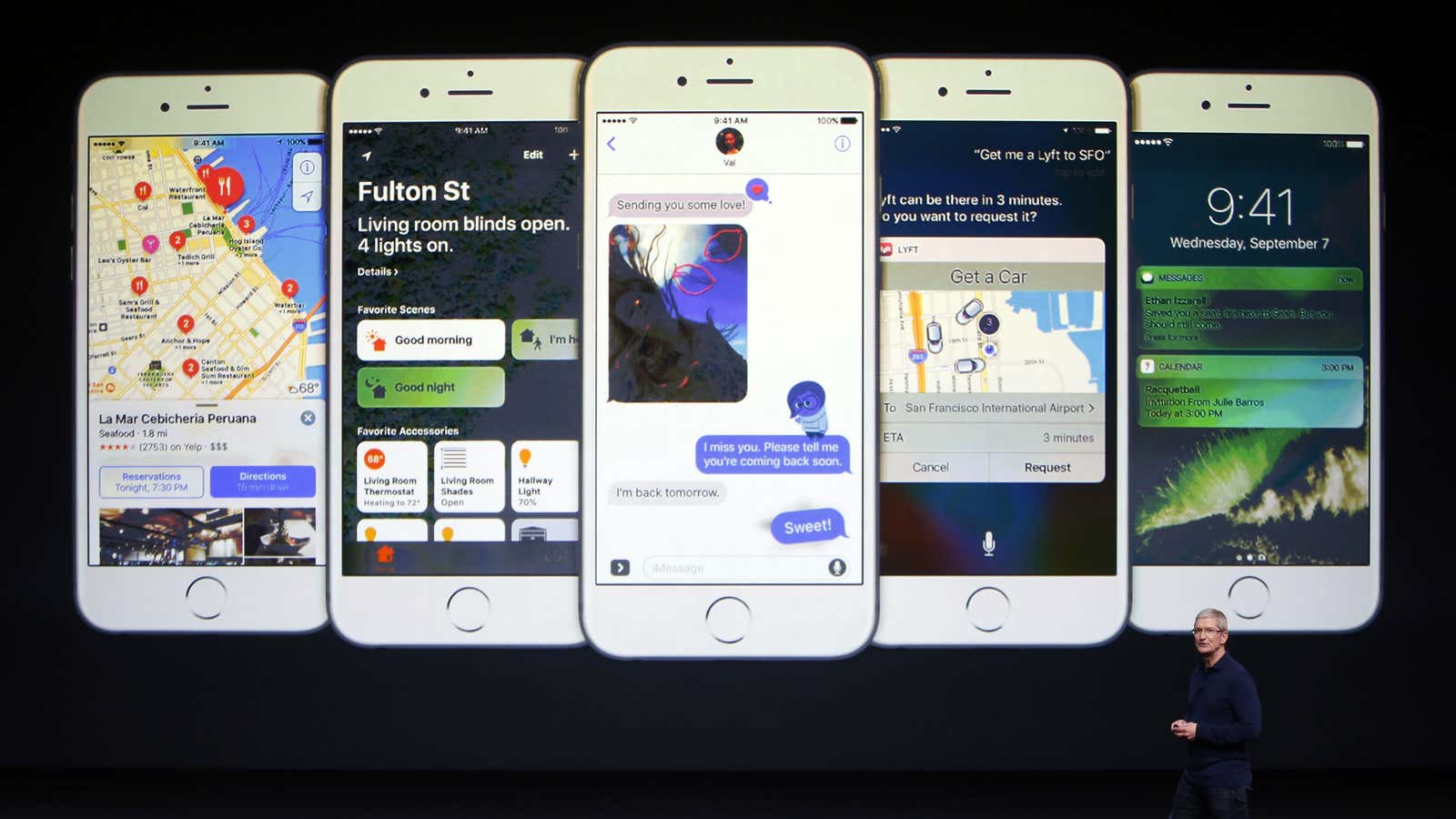

And so when Apple releases iOS 10 today—a milestone update for one of the most important devices of the last decade—I want only one thing. No, not a more accurate step counter for the Health app, or a faster shutter speed for the camera. I’m not even asking that iOS 10 forego the years-old ritual of using updates to cripple operating speeds of older model iPhones. I want profanity and similar words to be recognized by the predictive text algorithm.

In his 1934 essay “An Obscenity Symbol,” Allen Walker Read attempts to explain the taboo of profanity: “The determinant of obscenity lies … in the attitudes that people have towards these things.” And if The Wire has taught us anything about culture, we know that “fuck” and its uses today is able to transcend the purely obscene.

What is perhaps most galling about Apple’s decision to exclude profanity from predictive text is that the very act of doing so represents an obdurate and wrongheaded attempt at determining for us the legitimacy of words in regular usage and how we speak. Profanities have a place in the dictionary—they have etymologies and cognates, earliest dates of use, conjugations. Their impact should have no bearing on whether they are recognized as parts of the English language. Language, like the rest of the world, is full of ideas we might find uncomfortable, but cannot retreat from.

Even if we are able to entertain or justify a hypothetical argument against profanity’s place not only in our speech, but as words recognized by canonical dictionaries, there is still no question that words like “testes” or even “ejaculate” (the latter can be used to describe a way of speaking) belong to the lexicon of medical and sexual science. And yet, each of these need to be typed out in their entirety because the iPhone’s predictive text doesn’t want to recognize them. Which makes me wonder if maybe Apple just finds these words icky.

If Apple has become the moral arbiter of regular usage, then it also assumes for itself the ultimate responsibility of deciding which words are relevant to our conversations. If, God forbid, we say something too obscene, Apple is there to remind us that we didn’t really want to say it.

This level of editorializing is largely absent from Apple’s app store, where you can download dozens of free dating and hookup apps in a matter of seconds, not to mention Snapchat, the longtime standby of the nude-pic-sending era. Presumably the logic here is that as consenting adults, we should have the choice to use our phones to suit our own needs. So why doesn’t this choice exist when it comes to vocabulary? Why the hangup about naughty words?

Of course, given the growing number of children who are using smartphones, a simple argument in favor of autocorrect and predictive text restrictions is a sort of think of the children approach to technology. We can’t and shouldn’t want to make it any easier for children to swear at their moms via text, nor do we want a 5-year-old who has been handed an iPad and told to keep quiet accidentally opening adult webpages after a search bar autocorrect mixup. But then of course, we’d be crazy to forget that giving smartphones to children is also giving them access to the internet—a place that has allowed pornographers to take an if you build it they will come approach to their creative choices. Moreover, Apple is known for user-friendly interfaces. With two clicks you can locate your lost phone with your desktop, and therefore with similar ease engage a theoretical parental control switch that could disable the bad language protocol.

But Apple’s discomfort with swearing isn’t just about kids. Apple wants to dictate the way adults speak too. Its autocorrect and predictive algorithms are capable of learning our individual vocabularies. Over the years, it has learned to offer me a predictive text option and to make autocorrect changes for invented nicknames between friends, words I have created, phrases typed out in syntactically catastrophic French to my dad. It has even quickly learned the word Fuxk from the few times I made a typo, offering it to me regularly in the form of autocorrect. And yet it refuses to learn the original profanity even after years of my typing it out correctly. Apple doesn’t want me to swear, or perhaps doesn’t want to appear to condone it.

Given the mechanics of an iPhone’s keyboard, an abnormally high percentage of words typed out are subject to some form of correction. It is a system that, quite brilliantly, has failure built into its mode of operation. But this also means that, by necessity, it understands patterns of typos and which words are most likely to be misspelled, and how. The exclusions are clearly deliberate. The greatest irony is that once these words are typed out, they are never adorned with the red scribble that hangs below misspelled words. Which is to say, Apple understands that these words are real, but still wishes to have nothing to do with them.

“Is it possible for a word to be obscene by nature, in and of itself?” Read asks in his essay. Apple seems to think so. And yet more than 80 years ago, in 1934, Read suggested “no normal person” would find either sex or basic functions of the body inherently obscene. They are instead, he says, completely natural. Still, Apple decided that this definition of obscenity and taboo was far too narrow. Why not lump basic anatomical and menstrual vocabulary in as well?

This is a company that literally stole the breath from a room of jaded and cynical tech writers and developers when Steve Jobs pulled the newest MacBook Air out of a manila interoffice envelope as a demonstration of its reduced size and weight. But how can a company that purportedly exists at the forefront of consumer technology justifiably hold such a puritanical notion of regular usage? The record for obscenity in a single film was established by South Park in 1999 and has been broken many times over since then.

And yet Apple—purveyors of shiniest, sleekest pieces of technology that would make the Jetson family envious of an average college freshman—pretends we don’t swear. It pretends we don’t get angry, or have base emotions, and that we don’t even talk about our reproductive or sexual health; that we don’t enjoy orgasms or have testes or use tampons. We don’t text family physicians urgent questions, or ask our partners to buy condoms. Apple pretends we live in a world where, when excited, we use wonky catch phrases like Holy shirt or That’s ducking incredible. This is the world Apple would have us live in.

We certainly don’t masturbate or ever talk about it. Apple assumes the human race is more likely to discuss Nasturtiums—a genus of flowers— by text than we are to masturbate. If you continue spelling the word manually, the predictive text function then offers up “Mad turbulence,” and, eventually, “Mad turbans.” According to Apple, we are botanists first, frequent flyers second, and racists third—but the thought of masturbating has never crossed our minds.