Right versus pragmatic

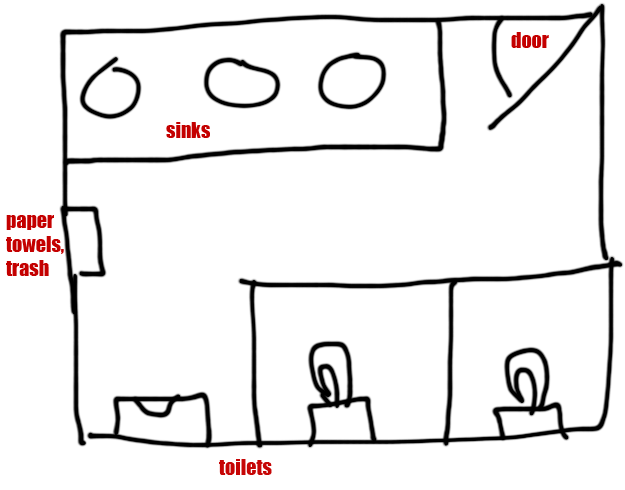

At a previous job, the shared men’s bathroom for the floor was laid out like this:

(Please excuse my drawing skills.)

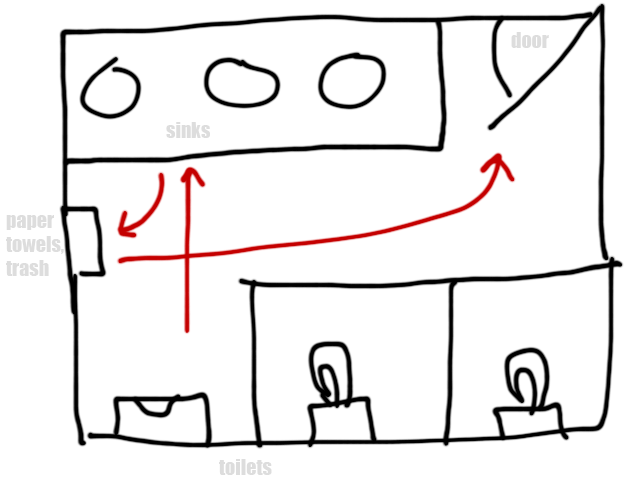

When we were done doing our business, this is the path we’d take:

Many people don’t like touching bathroom doorknobs after washing their hands. (Understandable.) But some of them dislike it so much that they’ll take their paper towel over to the door, turn the knob with it, and throw it on the floor while exiting.

By the end of the day, there would be paper towels all over the floor by the door.

One of the floor’s tenants attempted to solve this problem by posting passive-aggressive notes on the paper-towel dispenser.

The signs never worked. Instead, they just annoyed and angered people. Some people even threw more paper towels on the floor because they didn’t like the condescending way they were being instructed.

There was no chance the signs would ever work. The people who threw paper towels on the floor knew that it was “wrong”. Maybe their desire to avoid touching the doorknob was stronger than their desire to do the “right” thing every time. Or maybe they just didn’t give a damn about making the bathroom slightly worse for someone else to make it slightly better for themselves. Either way, a sign’s not going to solve the problem, because the problem isn’t that they didn’t know the right thing to do. They knew what they were doing, and for whatever reason, they didn’t care.

This problem wasn’t solved by the time I left that office. It probably still isn’t.

The pragmatic way to solve the problem would have been to adapt to what these people were going to do anyway: just put another trash can by the door.

They never tried that. They just kept posting more signs, because they were convinced that they were right.

This pattern is common. We often try to fight problems by yelling at them instead of accepting the reality of what people do, from controversial national legislation to passive-aggressive office signs. Such efforts usually fail, often with a lot of collateral damage, much like Prohibition and the ongoing “war” on “drugs”.

And, more recently (and with much less human damage), media piracy.

Big media publishers think they’re right to keep fighting piracy at any cost because they think it’s costing them a lot of potential sales.

It is, but not as many as they think, and not for the reasons they think.

The Oatmeal’s awesome comic illustrates the problem well: demand is rapidly increasing for accessing movies and TV shows outside of their traditional distribution channels, and rather than addressing this demand, the publishers are making it even harder to get their content legally in these contexts.

This is like trying to solve the paper-towel problem by moving the trash can even further away from the door.

Not all piracy represents lost sales: many pirates would never have paid, and would rather go without whatever they can’t easily pirate. That’s not a market worth worrying too much about, because there’s not much anyone can do to stop it, and any attempts to slow it down usually just limit, inconvenience, frustrate, and anger the paying customers.

But there are a lot of people who will pay to get content legally, even if it’s easy to pirate, when getting it legally is easier. (This is now the case, to a large extent, with music.)

In response to The Oatmeal’s comic, Andy Ihnatko makes a good counterargument:

The single least-attractive attribute of many of the people who download content illegally is their smug sense of entitlement. …

The world does not OWE you Season 1 of “Game Of Thrones” in the form you want it at the moment you want it at the price you want to pay for it. If it’s not available under 100% your terms, you have the free-and-clear option of not having it.

Andy’s right. But it’s not going to solve the problem.

Relying solely on yelling about what’s right isn’t a pragmatic approach for the media industry to take. And it’s not working. It’s unrealistic and naïve to expect everyone to do the “right” thing when the alternative is so much easier, faster, cheaper, and better for so many of them.

The pragmatic approach is to address the demand.